Credit: Cliff Hawkins/Getty Images; Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

Some athletes in Tokyo are indulging in a trendy technique to enhance the effects of training and stimulate recovery. Credit a Japanese former power lifter.

Every four years, the Summer Olympics shows the world the latest training or recovery method the greatest athletes have taken up.

In 2016, many swimmers had red circular marks on their skin from “cupping,” an ancient Chinese practice involving suction on sore muscles and tendons.

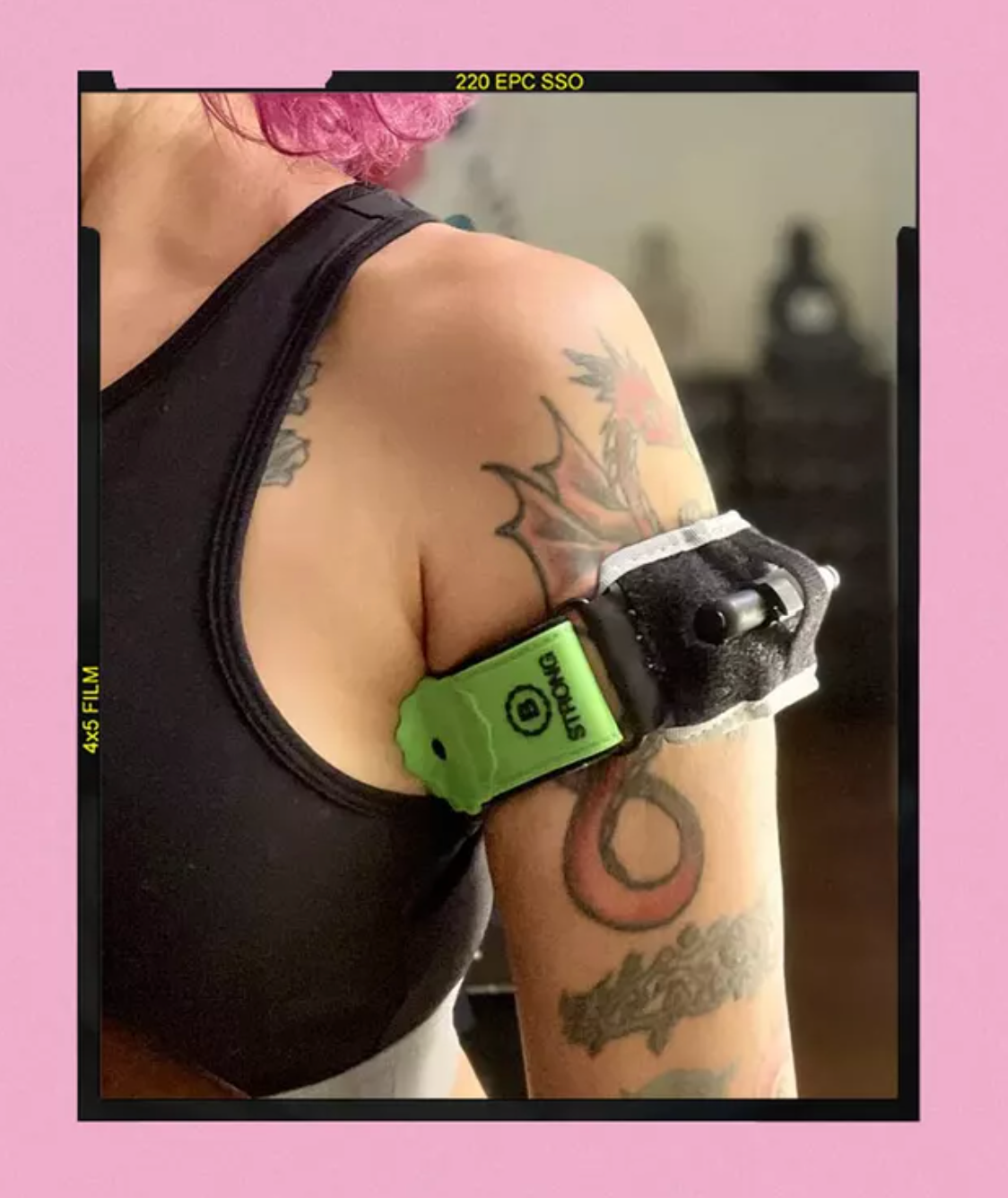

This year, the hot thing appears to be tourniquets.

No, there is no outbreak of cuts. But the American swimmer Michael Andrew is wearing tourniquet-like bands in the practice pool. Galen Rupp, the defending bronze medalist in the marathon, sometimes straps similar bands to his legs while training.

They are among the elite athletes who have become disciples of a practice known as blood flow restriction, which is exactly what it sounds like: cutting off blood flow to certain muscles for limited periods to both enhance the effects of training and stimulate recovery.

The practice has come into vogue in time for the Tokyo Games, and a Japanese former power lifter named Yoshiaki Sato, who developed it in 1966, is finally having his moment.

Sato, 73, has been honing the technique and spreading its gospel for most of his adult life, building a small fortune in the process as a Japanese version of Jack LaLanne. He has created a practice and a series of products called Kaatsu that are geared toward blood flow restriction. Sato still practices blood flow restriction every day, and now marvels at the attention it is getting.

“It was always just a matter of time,” he said this month in an interview from his home in Fuchu, a suburb of Tokyo. “I just did not think it would take this long.”

In recent years, blood flow restriction gained an important advocate across the Pacific in Dr. Jim Stray-Gundersen, a physician and sports medicine researcher who has worked closely with Olympic organizations in the United States and in Norway.

He essentially created the “live high, train low” approach to altitude training, which prescribes athletes sleeping and living above 8,000 feet to increase the production of oxygen-carrying red blood cells, then descending a few thousand feet to train in order to avoid overtaxing the body.

Stray-Gundersen trained with Sato earlier in the past decade and became known as the “Kaatsu master” before the two parted ways. Stray-Gundersen then created his own blood flow restriction methods and a company, B Strong, in 2016.

“You can get the benefits of swimming 10,000 yards by swimming maybe a thousand,” he said recently.

Andrew, 22, a rising star who will swim three individual events and participate in relays in Tokyo, said he first started experimenting with blood flow restriction five years ago at the urging of Chris Morgan, a veteran swim coach.

Credit: Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times

He often straps the bands onto his arms for 25-yard sprints and tries to achieve the same times as when he is not wearing them.

“Obviously, it’s very difficult,” Andrew said in an interview this month. “But you are simulating a sensation of real pain that tricks the body into regrowth.”

The swimmer entered a small business relationship with Sato’s company after years of using its products. (If a customer uses Andrew’s code, Kaatsu donates 20 percent of the sale to Andrew’s swim club.)

Before and after training and races, Andrew straps a gadget high onto each leg, then increases and decreases the tension of the tourniquet at regular intervals — think of a blood pressure cuff — to stimulate blood flow and recovery. Sometimes he wears the bands in the ready room before heading out to the pool deck for a race.

Not everyone has jumped on the bandwagon. Dave Marsh, who has coached numerous swimmers to the Olympics and is directing Israel’s team in Tokyo, said one of his athletes had used blood flow restriction for recovery and rehabilitation from injury, but he had yet to recommend it in training.

“The first job of a coach is to not do any harm,” Marsh said. “It seemed to me that with blood flow restriction, it could lead an athlete to take a step backward.”

Like any good sports scientist, Stray-Gundersen wanted to see the data when a colleague told him that blood flow restriction was helping his athletes build muscle mass in two weeks that normally took six. As it turned out, there was a paper from 2000, published by Sato and scientists at research institutes in Japan, in the Journal of Applied Physiology.

Put simply, the paper argued, blood flow restriction prompted an outsize response from the brain to speed up the normal process of repairing and rebuilding damaged tissue.

Cutting off blood flow, then switching it back, can spur the brain to use more healing powers than it would normally think it needs.

Since that study, a number of independent researchers have confirmed the potential benefits of restricting blood flow during exercise. Shawn M. Arent, the chairman of the Department of Exercise Science at the University of South Carolina, is currently conducting a study on its effects for the Defense Department.

He said early trends suggested that the practice might be most effectively applied when athletes wanted to dial back their training load without sacrificing fitness, either while tapering before competition or at the end of a season, while recovering from injury.

“It’s a good supplement for training; it’s not all of your training,” Arent said. “It provides physiological stimulus when other things might be limited.”

Sato said he accidentally discovered the benefits of blood flow restriction more than 50 years ago, during a Buddhist ceremony in a Japanese temple that required him to sit on the floor in the seiza position — bent knees with his heels under his rear end — for long periods. His calves and toes began to tingle, and he could no longer stand the pain after 45 minutes. When he stood, he saw his calves pump up with blood, and his legs felt as they did during a workout.

Sato thought perhaps there might be some connection between cutting off blood flow to muscles and training them. He began tying karate belts and later bicycle inner tubes around his legs and performed a series of experiments, tracking how much the circumference of his thighs and calves would grow even when he performed fewer repetitions.

In 1973, Sato broke his ankle while skiing and restricted blood flow to the area during rehabilitation, letting it rush in periodically. A recovery that doctors told him might take four months took a little more than one.

“Pressure on, pressure off,” he said. “The benefits for both training and recovery was understood.”

For someone like Andrew, who swims thousands of yards every day, or Rupp, whose regimen includes more than 100 miles each week plus weight training and core work, or Noah Syndergaard, the pitcher for the Mets, or Mikaela Shiffrin, the champion skier, or any of the other top athletes who have started incorporating blood flow restriction, the technique allows them to reduce the likelihood of a repetitive stress injury and speed up recovery time.

For Andrew, the most important part of the technique may be how strongly he believes it works. As every sports scientist knows, placebos can often be as strong as any drug.

“I did something like 18 races in seven days at the trials, and I felt fresh,” Andrew said. “I’m sure it was because I was so disciplined with the recovery. I used it all the time.”

SOURCE:

Matthew Futterman